Although it tells the story from thousands of years ago, the story of Esther is surprisingly contemporary. Let’s look at a few rabbinic discussions about the Purim story, and see if they feel familiar…

What were their names?

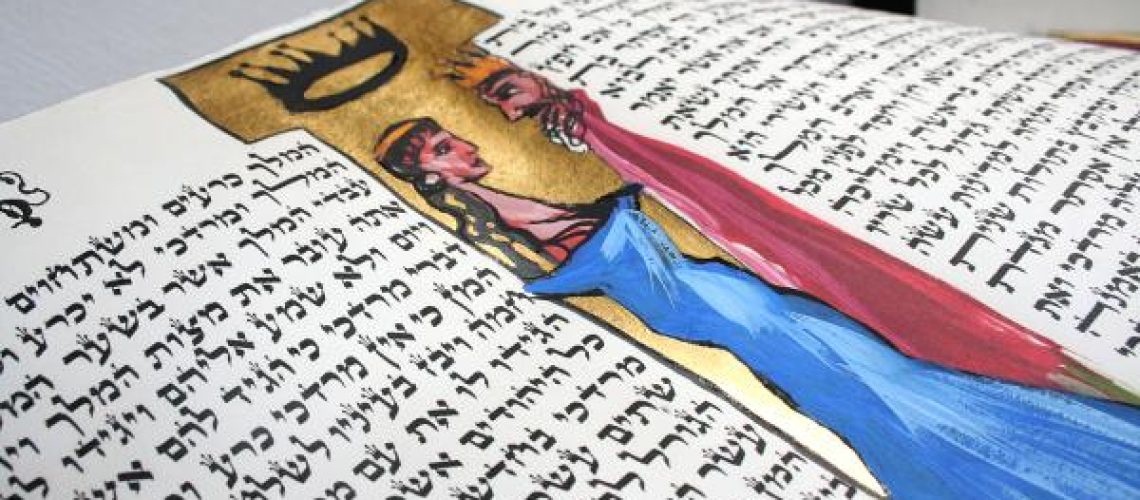

The heroine of the Purim story is introduced as “Hadassah, who is Esther”, living with her cousin Mordekhai (who might have also been called Petachia). Why does she have two names? European Jews have had a similar practice for centuries – one name for the outside, and one in the synagogue. Ishtar and Marduk were two major Babylonian gods, and having the names Esther and Mordekhai might have been a bit like being called Jean-Paul and Christine today.

What did Esther eat in the palace?

The Talmud (Megillah 13a) discusses Esther’s diet in the palace of Ahasuerus, and presents three opinions. One rabbi claims that she ate kosher meat, a second says that she ate fatty pork, and a third that she ate seeds and vegetables. No definitive answer is given. We can see this as three models for Jews living in a non-Jewish society, and the difficulties of balancing between the different expectations.

What did Esther look like?

The book simply says that she was “of beautiful form and fair to look on… and obtained favour in the sight of all them that looked upon her.” The Talmud adds that everyone who saw her thought that she belonged to their own people. Stereotypes aside, there’s no one way to look Jewish. This ambiguity has always led people to project their own fantasies and fears onto the Jews, leading to fetishism and antisemitism.

Why did the king agree to destroy the Jews?

Haman makes the old antisemitic argument: “There is a certain people scattered abroad and dispersed among the peoples in all the provinces of thy kingdom; and their laws are diverse from those of every people; neither keep they the king’s laws…” Their crime is being different. They have a different calendar, different foods, different stories, different practices – but they look like us! Ahasuerus strives for uniformity and absolute power, and this claim of a difference convinces him that the Jews are superfluous.

Who wins in the end?

The book of Esther ends with a strange fact: that the king raised taxes throughout the lands of his empire. In contrast to Pesach or Chanukah, there is no real victory. Yes, Haman is destroyed and so are those who try to attack the Jews, but the final image is that of a strong and wealthy Persian king. The Jews are temporarily saved, but there is no guarantee that they will not be persecuted again.

So why do we celebrate?

The children’s version of Purim is that we were in danger and then we weren’t, so now we celebrate and make lots of noise. A more adult version is that we recognise how fragile, precarious, rare and…. ridiculous are lives are! Most of the year we live our lives normally, confronting the challenges and the beauty of the world, but not thinking too much. But on this day, we have the opportunity see past any illusions, and accept the bizarre miracle of our existence.

And this year?

If we accept Purim as eternally relevant, we need to carefully draw parallels between that story and our one, our ones, because we have many. Certainly, Jew-hate and projections are happening all over the world, and the precarity of our lives in this world has been made evident over and over again. Certainly, the irresponsible fantasies of revenge played out in the book of Esther are as dangerous as they always were. The fasts and feasts of Purim are serious, not an escape from reality, but an invitation to re-learn a certain perspective and engage with reality with pride, courage, responsibility and laughter.